Pinned to the Cause: The Political Power of a Simple Accessory

- Synergy Magazine

- Nov 22, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 12

By Grace Johnson | Photos by Lola Wucherpfennig |

Since the start of election culture in America, citizens have expressed support for political candidates through fashion; most notably, by wearing pins and buttons. These campaign pins help to contextualize iconic periods throughout American history.

Campaign Button History

The first iteration of American political pins was promoted during George Washington’s presidency. Citizens wore clothing buttons with the slogan “Long Live the President” arranged around a circle of stars to symbolize their freedom from the King of Great Britain.

It wasn’t until Abraham Lincoln’s run for Presidency in 1860 that a photo of the candidate appeared on the pin. This was due to the switch in materials- from clothing buttons to tintypes. Also known as ferrotypes, these pins were made of tiny photographs developed on thin sheets of tin, and were more durable than the buttons used previously.

However, access to these pins was still limited, as production was rather time-consuming. The election responsible for the surge in political pins happened in the 1896 McKinley vs. Bryan Presidential race.

McKinley’s campaign team was able to patent and mass produce campaign buttons for the first time due to a new material called celluloid. This artificial plastic-like material covered the front side of the button and allowed for a cheaper production process.

This style of buttons was prominent until the 1920’s when a cheaper method was introduced. This time, images were directly printed onto sheets of metal and then shaped into a button. These were called lithograph buttons and are still frequently seen today.

The ability to efficiently make large quantities of pins allowed for mass distribution across the nation, skyrocketing the popularity of campaign buttons. This increase in accessibility and use of pins has transcended past just a political statement; it has provided a creative way to promote various social movements and express individuality.

Anti-War

Anti-war and anti-nuclear pins from the 1960’s. PHOTOS: DECADES OF RESISTANCE: POLITICAL MOVEMENT PINS COLLECTION, HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL LIBRARY & RESEARCH SERVICES.

In the 1960’s, “Grassroots” buttons – simple pins easily produced by citizens – were popularized due to the era’s Anti-war Movement. These pins promoted candidates or shed light on social issues, hallmarked by the U.S.’s involvement in Vietnam at the time.

Civil Rights and Racial Justice

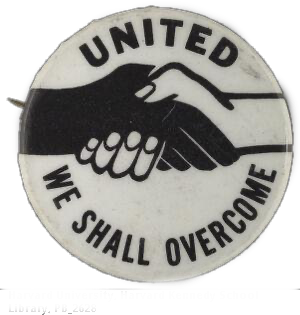

“United We Shall Overcome” pin from the 1960’s and “March on Boston” pin from 1974. PHOTOS: DECADES OF RESISTANCE: POLITICAL MOVEMENT PINS COLLECTION, HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL LIBRARY & RESEARCH SERVICES.

The Civil Rights Movement was a fight for equality and justice for Black Americans that started gaining traction in the 1950’s.

The slogan “We Shall Overcome” is featured on a protest button from the 1960’s. The phrase originates from Minister Charles Albert Tindley’s 1901 song, “I’ll Overcome Someday,” which found popularity among enslaved individuals of the early 20th century, and eventually became a common church song. “We Shall Overcome” is a version of the phrase popularized during the Civil Rights Movement that found its home on political buttons of the Movement.

Similar to the start of the Vietnam War oppositions, this Movement mainly consisted of grassroots organizers leading demonstrations across the country. One of these fights for racial equality involved mandatory urban desegregation through compulsory busing in the city of Boston.

In the mid 1970’s, Boston Public Schools were required by law to desegregate schools through a busing system. This was twenty years after the passing of Brown v. Board of Education which was issued on May 17, 1954. This date was often referenced on buttons as a way to commemorate the event, but also shed light on the need for more progress towards racial equality.

Women’s Rights

“59¢” pin from the 1960’s and “Mobilize for Women’s Lives” pin from 1989. PHOTOS: DECADES OF RESISTANCE: POLITICAL MOVEMENT PINS COLLECTION, HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL LIBRARY & RESEARCH SERVICES.

The fight for women’s rights is often defined by the four waves of feminism. While the first two waves assured certain rights for white women, women of color were excluded until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Notably, the Movement gained much of its strength from the Civil Rights and Anti-war protests.

Up until the Equal Pay Act in 1963, there was no legislation guaranteeing equal pay between men and women. For every dollar a man made, a woman made 59 cents. A common way to highlight this pay gap was by displaying “59¢” on protest buttons, which helped the Movement gain exposure.

The momentum began to slow after the Equal Rights Amendment did not pass in 1982. The prevalence of feminism came back in 1989 after a Missouri anti-abortion law went to the Supreme Court.

In response, the National Organization for Women (NOW) teamed up with grassroot organizers to set up a march for abortion rights. There were several promotional pins made for this event which helped garner national attention. The protest remains NOW’s largest demonstration to date, highlighting the significance of these pins for the Feminist Movement.

LGBTQ+ Rights

“National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights” pin from 1979 and “From all Walks of Life” pin from 1986. PHOTOS: DECADES OF RESISTANCE: POLITICAL MOVEMENT PINS COLLECTION, HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL LIBRARY & RESEARCH SERVICES.

The Stonewall rebellion in 1969 paved the way for an era of queer visibility continuing into the next decade. On the one year anniversary of Stonewall, pride marches erupted in major cities across the US to advocate for equal rights.

A decade after the start of the Stonewall rebellion, the first National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights took place in Washington DC. This event attracted thousands, estimated to be between 75,000 and 125,000 attendees. Many pins used to promote this event depicted the Capitol building in the background, which represented the fight towards protective legislation for LGBTQ individuals.

Despite the milestone achievements, the LGBTQ Movement experienced a dramatic shift after the start of the AIDS epidemic. In response to this, individuals in the LGBTQ community created ACT UP, which stood for the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. This group was responsible for many protests and demonstrations throughout America, advocating for the lives of queer people.

Many political pins during this time were more solemn compared to previous decades, but they highlighted the need for queer solidarity. This notion has transitioned into more modern times with the use of pronoun pins, as they promote individuality while also providing a safe and inclusive space within the LGBTQ community.

Works Cited

Cave Creek Museum. "Political Campaign Buttons." Cave Creek Museum,

www.cavecreekmuseum.org/political-campaign-buttons/. Accessed 9 Nov. 2024.

ArcGIS StoryMaps. "The Story of Political Campaign Buttons." ArcGIS StoryMaps,

storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/cfa65c76822d481ea76ae7a250b6cb30. Accessed 9 Nov.

2024.

JSTOR Daily. "A Message in a Button." JSTOR Daily, daily.jstor.org/message-in-a-button/.

Accessed 9 Nov. 2024.

University of Delaware Library. "Campaign Buttons." Exhibitions | University of Delaware,

Accessed 9 Nov. 2024.

Harvard Kennedy School. "Political Buttons." Harvard Kennedy School Library & Knowledge

ions/political-buttons Accessed 9 Nov. 2024.

Comments